DMTN-227

The Consolidated Database of Image Metadata#

Abstract

This document proposes a specification for what the content of an image metadata database should be, how it should be managed, how it could be implemented, and how it might be extended. A phased strategy for bringing it to production is also proposed.

Background#

Originally, the Consolidated Database was a way to efficiently administer a large number of independent database instances that were expected to be needed for services as well as processing. By placing all of these instances on a single relational database management system (RDBMS) server, efficiencies of storage management and administration were expected. Of course, centralizing so many services, some critical, creates requirements for high availability and high performance, but Oracle Real Applications Clusters (RAC) was expected to meet those needs.

Today, administration of service-local database instances is relatively simple, and the benefits of distributing these to minimize side-effects outweigh management issues. As a result, we expect to deploy service-specific databases in Kubernetes, often of differing server technologies, whether for the Data Butler, TAP Schema, the Engineering and Facilities Database (EFD), the Alert Production Database, or Gafaelfawr.

One database instance that was to be part of the Consolidated Database has not been fully defined, however. That database contains raw image metadata for exposures and visits. Since the raw data product of the Observatory and its Camera is images, this metadata is critical for both operational processes and science understanding. This raw image metadata database has come to take on the name “Consolidated Database” as it potentially consolidates information from a variety of sources, including the full range from Summit systems to Data Release Production (DRP).

While image metadata is a primary purpose of this database, the Consolidated Database also needs to store additional “conditions” information about the state of the Observatory and its environment that will be summarized across dimensions other than the exposure/visit axis. The summarization dimensions used can include regular time windows (e.g. per-minute) as well as variable windows such as telescope movements (so-called “TMAEvents”). This information has the potential for being very large, so appropriate selection and summarization will be required. Much of this data may be useful for engineering purposes only, so it may not be exported as part of a Data Release (DR).

This document proposes a specification for what the content of this database should be, how it should be managed, how it could be implemented, and how it might be extended. A phased strategy for bringing it to production is also proposed.

Raw Image Metadata#

Raw image metadata includes information about the conditions under which the image was taken, such as timing, temperature and weather, filter, voltages, etc. Raw versions of this information are produced by Summit systems and published to the EFD.

Previously, the Transformed EFD has been defined as the result of a service that will derive appropriate metadata for an image and publish it along with image identifiers. A proposal for how to do this transformation was drafted, but it is lacking at least one critical feature: relating the transformed data to raw images, rather than arbitrary time intervals.

The Consolidated Database system will contain a service that summarizes the EFD telemetry according to exposure and visit time windows. Because telemetry may be published at intervals that do not align with the exposures/visits, additional data points before and after the exposure/visit time window may be necessary to compute the summary value. While many values can be summarized using standard aggregators such as mean, median, minimum, and maximum, calculations may also involve interpolation, extrapolation, or model-fitting.

The Large File Annex (LFA) of the EFD can contain datasets that are captured on a per-exposure or per-visit basis. Most of these datasets are expected to be ingested into the Data Butler, and so they will not be stored in the Consolidated Database. But there may be certain datasets that for latency or other reasons should be loaded into the Consolidated Database. One of these LFA datasets is the Header Service output. The Header Service is the source of truth for the information used by Prompt Processing and has the lowest latency of any EFD summary. Accordingly, its output will be loaded into the Consolidated Database by a Summit service. Note that certain metadata provided by the Header Service may have more accurate values that can be computed later by the EFD summarization service; both will be retained.

Raw image metadata also includes information about the initial intended purpose of the image, which can indicate the kinds of processing that are relevant. Some of this information comes from the Scheduler or is provided to the Camera Control System via an image type string that eventually is captured in a FITS header.

Comments by observers that are relevant to a particular image and other annotations by humans or automated systems should also be captured. The Observing Specialists capture this information in the Summit “exposure log” and “narrative log” databases. These need to be considered part of the Consolidated Database.

Raw image metadata can also include metrics or other derived quantities resulting from processing that are nevertheless characteristic of the image, rather than of the processing itself. This processing may occur at prompt (second to minute) timescales or at longer timescales ranging up to Data Release Production that may occur 10 years after the image was taken. An example of this is telescope mount azimuth jitter, which will be computed by the Rapid Analysis system as an average over the visit timeframe and then published to the Consolidated Database.

Note that there are many sources of metadata operating on a variety of latencies and that all metadata may be recalibrated, recomputed, adjusted, edited, and corrected over time. This even applies to metadata that has been published as part of a Data Release; while we would generally apply any updates to the next year’s Data Release, it is conceivable that the metadata might need to be “patched” for an existing DR.

All of this metadata is unified by its pertinence to a given image. However, the Standard Science Visit is composed of two “snap” images with the same telescope pointing that are processed together as if they made up one single exposure of twice the length. Accordingly, it makes sense to also summarize metadata by visit as well as raw image (exposure). If it turns out that all visits are composed of a single image, as specified in the Alternate Science Visit definition, then these two tables collapse to one. If other visit definitions (where combined image metadata makes sense, not just groupings of exposures for processing) end up being used, those could be stored in the same visit table or a parallel one, but this scenario seems unlikely at this point. Visit definition for this purpose needs to be consistent across all systems that use the metadata. For metadata about image groups that are not visits, see below about general datasets.

In addition, we often process images in a detector-parallel fashion. As each detector’s image can be handled independently, and the available detectors could potentially change from image to image, having the ability to store metrics and metadata at the detector level is important.

Finally, the Camera has smaller amounts of information that is reported on a per-raft or per-REB (rear electronics board) basis for each image.

Logical Schema#

Visits and exposures are the key dimensions for two sets of tables.

Since detector, REB, and raft information potentially arrives independently, storing this as columns in a wide row would require updates in place. It is better to have more normalized, smaller, separate detector/REB/raft-exposure tables instead. It is possible that a detector-visit table may also be needed.

Of course these tables are replicated for each instrument: LATISS, LSSTComCam, and LSSTCam.

Other information derived from raw images, including single-frame Source catalogs, mask planes, etc. are not metrics or metadata about an image or visit and so do not fall into the domain of the Consolidated Database.

Similarly, while metadata about calibration images is part of the Consolidated Database, combined calibration images, linearizer models, and other calibration outputs are not.

Summarized EFD#

In addition to the exposure/visit-summarized EFD described in the previous section, the Consolidated Database will include selected EFD contents summarized over fixed time windows and over other variable-window time dimensions (Events).

Note that this is the only access science users will have to the EFD, as the internal InfluxDB time-series databases will not be accessible as part of the released data.

The initial goal for fixed-window summarization will be to provide low-rate (less than 1 Hz) commands, events, and telemetry as individual data points. Higher-rate streams would be summarized over 1 second or longer intervals.

Selected EFD topics will be summarized over pre-defined Event dimensions, with the code defining those dimensions (based on EFD topic values alone) to be provided by external groups within Telescope and Site Software (TSSW), System Integration, Testing, and Commissioning (SIT-Com), or System Performance (RPF).

Uses#

Raw image metadata is used to report to humans, to feed back to Summit systems such as the Scheduler, and to filter images for processing.

In particular, it is of significant use for Campaign Definition. In that regard, extending the concept to apply to metadata for other datasets such as catalogs may also be useful.

Reporting and Feedback#

All metadata from SAL events is already available as part of the EFD. It is also available to other Commandable SAL Components (CSCs). Some of this information is tagged with relevant exposure or visit identifiers, but much is not. The Transformed EFD is meant to provide tagging where it is not already present.

Quality metrics derived from Prompt Processing are similarly published to the EFD. These will always be tagged with exposure and visit identifiers.

These metrics need to be summarized and correlated at the Summit for the Scheduler, for observers, and also for Survey progress monitoring.

Campaign Definition#

The datasets used as inputs to pipelines will often need to be filtered and sometimes grouped based on properties or metrics that have been determined or computed previously. Common examples are exclusion of images that do not meet quality metric thresholds; inclusion of images that belong to a particular science program; selection of images that meet the criteria for a co-add; or pairing of intra-focal and extra-focal detector images (within a visit or across visits) for wavefront processing. The ultimate source of the image selection information could be a header, a Parquet table, or even something external to Science Pipelines. This filtering/grouping may be specified at the Campaign Definition level, but ultimately the pipeline execution (graph generation) needs either to have this capability or to be able to incorporate its results.

Processing#

Currently “visit summary tables” are prepared during Data Release processing. This information should be stored in the Consolidated Database.

It might make sense to retrieve visit summary data from the Consolidated Database for use in downstream pipelines, but the pipeline Middleware has no provisions at present for obtaining datasets from a non-file data source. File exports from the Consolidated Database seem like a better way to retrieve this data, at least in the short term, even though it may be inefficient to scan through them and require more code to select the desired rows and columns. By using file exports, there is no question of synchronization of database inserts/updates and retrievals, provenance is simplified, and scalability is assured.

External Services#

The IVOA defines two relevant data models: Observation Data Model Core Components (ObsCore), which is combined with Table Access Protocol (TAP) to form ObsTAP, describing observations that have occurred, and Observation Locator Table Access Protocol (ObsLocTAP), describing especially observations that are projected to occur in the future. We need to serve observation data according to both of these models.

While these are conceived of in the IVOA documents as separate, but linked, databases, there is the potential to merge them into a single database. However operational concerns (including frequent updates by the scheduler and maintaining a wall between public and data-rights-only information) make it fairly clear that these should be distinct.

For ObsCore, we do not need to expose Butler component datasets in the metadata model. They can instead be exposed via IVOA DataLink services.

In addition to ObsCore, there is also the CAOM2 data model that is desirable to support as a de facto standard for released data products.

The Consolidated Database schema needs to be mappable to both ObsCore and CAOM2.

Architecture#

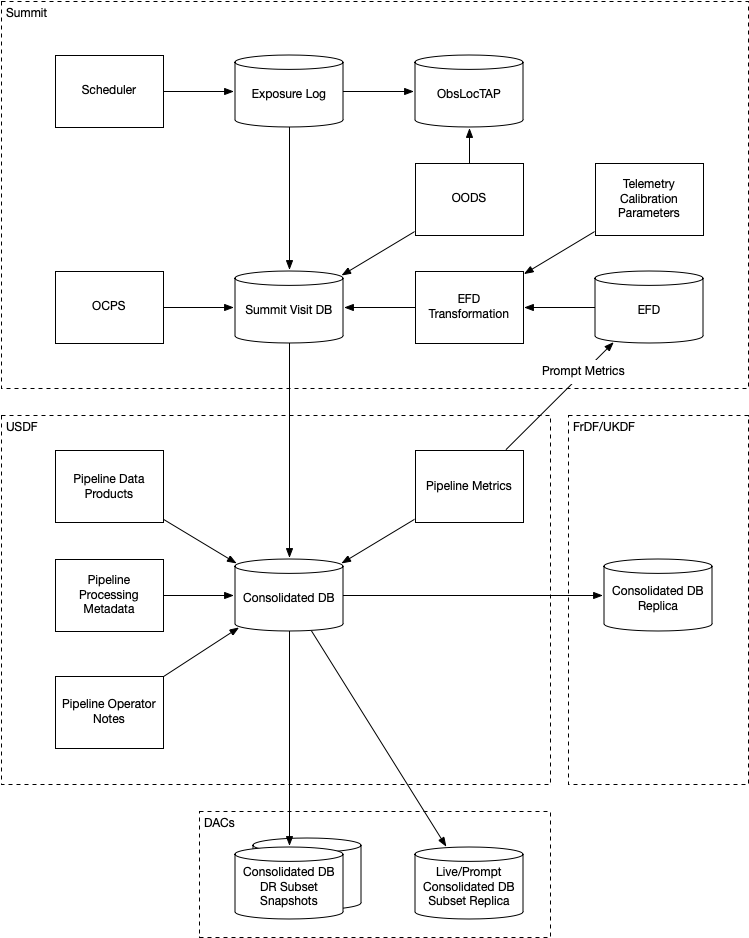

For the ObsLocTAP service, which is specialized and distinct from other uses, a separate Summit database instance will be used. While the information content derives from the Scheduler, it appears that the Exposure Log service already compiles this information, so it may be a more suitable basis. The public TAP front-end for this database could be located in the cloud; it does not need to be Summit-resident.

While conceptually a single globally-accessible image metadata database could be considered desirable, resilience and scalability require multiple, distributed, communicating database instances. In such a situation, the CAP theorem says that building such a system in a partition-tolerant and highly-available manner means that only eventual consistency can be enforced.

The Data Release needs are slightly different in that they are almost entirely read-only, with very rare additions. Joining with the other Data Release tables in systems like Qserv is required. This is better handled by using a snapshot of a subset of the live database rather than attempting to connect the live database directly. (Note that this could still be patched or updated by taking an appropriate snapshot of the new version.)

For testing purposes, small databases will need to be instantiated, loaded, and removed.

Metadata will conceptually contain wide fact tables with relatively limited dimensionality. There will be many, many columns of information for each image or visit, often with only a unique image/visit identifier as the primary key.

In all cases, the database will need to be updated as different sources provide information. These updates will be handled by providing separate tables for each information source. Effectively, the database will contain separate columns for each update, rather than rows with validity times or updates in place.

Views will be provided so that users can see pre-joined, denormalized, “wide” tables rather than per-data-source tables.

The sources of data at the Summit will include:

The Exposure Log, maintained independently but in the same database server.

The Header Service, via the LFA.

Metrics from Rapid Analysis, via Sasquatch.

The sources of data at the USDF will include:

The Exposure Log, augmented by campaign pilot and quality notes.

The Header Service and other LFA datasets, via the LFA replica.

Metrics from Rapid Analysis, via Sasquatch.

Metrics from Alert Production, Calibration Products Production, and Data Release Production, via Sasquatch.

The Transformed EFD, summarized by exposure/visit.

The Summarized EFD, summarized by fixed time window.

Tabular DRP outputs, via Parquet files.

Fig. 1 Consolidation of databases.#

Outputs will include snapshots for DRP in the form of Parquet tables.

The Data Access Centers serve read-only replicas of prompt-oriented column subsets of the Consolidated Database in conjunction with other Prompt data products as well as read-only snapshots of Data Release-relevant subsets (in particular, such subsets only include rows for visits and exposures that are part of the DR).

Butler Registry and Campaign Management#

We currently have one database that tracks information about all datasets used for processing: the Butler Registry. It would therefore seem reasonable to implement the Consolidated Database by extending that Registry database.

There are several concerns, however:

The schema may be more malleable than has previously been desired for the Butler Registry, with updates as new metrics are conceived, bitemporality, and instrument-specific columns.

We are currently planning to have different Butler repos with different Registry contents at each processing location. The Consolidated Database, on the other hand, should be the same at each location.

By extending the Registry beyond ingestion requirements, to include frequent updates asynchronous from dataset creation, it may add substantial complexity to the Butler.

It may not be feasible to provide ObsCore and CAOM2 as views on the Registry; materialized derived tables may be necessary (e.g. to handle different requirements for specifying the geometry of regions).

It is infeasible to insist that all information about a dataset that might potentially be used to select or exclude it from a processing graph be preloaded into the Registry in advance of knowing that it is needed for generating a particular graph. Some information may come from external systems and may only be known at graph generation time.

If a way can be found to provide for Butler Registry-based graph generation while at the same time keeping the Consolidated Database outside the Butler domain, the overall system might be simplified and made more resilient.

One mechanism for doing so might be to enable the Butler graph generation code to incorporate lists of detector-exposures, exposures, detector-visits, or visits derived from the Consolidated Database. For some uses, lists of groups of images might be useful. These lists could be explicit lists of primary key identifiers, or, if very large, could be implemented as boolean bit-columns; they could manifest as TAGGED collections in the Butler Registry. The lists would be presented to the Butler at graph generation time, not long in advance, but they could be persistent afterwards for provenance purposes. As long as WHERE clause conditions combining Registry-only columns and Consolidated Database-only columns are unnecessary (which seems likely, as the Consolidated Database should generally be a superset of the Registry), this should be adequate for filtering. By presenting a single, relatively narrow interface, the hope is that the graph generation code would require only limited changes. At the same time, the flexibility of data sources and filtering mechanisms available to the list generation tools is maximized. This is similar to what was proposed in DMTN-181 as part of Campaign Management.

General Dataset Metadata#

Once a raw image metadata database is defined, it makes sense to ask whether it should be extended to also include other types of images, such as co-adds, or even other types of file datasets, such as catalogs. Automated production of this metadata comes from the Pipelines, which already output metadata datasets to the Butler repo. It would be desirable to capture human-generated processing and quality notes.

The alternatives therefore seem to be an extension of Butler provenance or an extension of the Exposure Log. Concerns include scalability to the much larger space of all datasets, increased dimensionality and complexity of dataset identification, and complex relationships between datasets.

Implementation#

EFD Transformations#

Columns in the Transformed EFD could potentially include all of the channels available in the EFD itself. Specifically desired columns mentioned in LSE-61 DMS-REQ-0068 include:

Time of exposure start and end, referenced to TAI, and DUT1

Site metadata (site seeing, transparency, weather, observatory location)

Telescope metadata (telescope pointing, active optics state, environmental state)

Camera metadata (shutter trajectory, wavefront sensors, environmental state)

Program metadata (identifier for main survey, deep drilling, etc.)

Scheduler metadata (visitID, intended number of exposures in the visit)

Basic information is already placed in the image header at exposure (boresight, exposure time, filter). Other information needs to be summarized from EFD information during an exposure/visit (DIMM seeing, temps, weather).

Only some metrics are composable from exposure to visit (i.e. the visit values are derivable directly from the exposure values for a two-exposure visit). Others need to be computed separately for exposures and visits.

For channels with infrequent sampling, interpolation between points outside the exposure interval may be necessary. The interpolation method may change over time.

For other channels that report raw values, a lookup table or other transformation may be needed to calibrate the data. This table may of course change over time.

Some channels are expected to be computed by Prompt Processing: astrometry, PSF, zeropoint, background, and QA metrics. Note that QA metrics submitted to Sasquatch via the lsst.verify interface need to be distinguished between the real data and nightly/weekly test runs.

Loading into ConsDB from Sasquatch will occur via the Kafka JDBC Connector. Transformations can be applied at the Kafka level prior to loading.

Remaining Tasks#

Immediate#

Deploy Header Service loader at the Summit. Connect with Kafka to trigger on LFA Object Available events. Deploy initial Header Service schema at the Summit in the Butler Postgres database.

Deploy Header Service loader at the USDF. Note that Kafka message at USDF may arrive before object store replication.

Complete minimal “shim” client library for publishing and querying. Long-term, querying should be via TAP and publishing should be via Sasquatch.

Deploy Sasquatch connector at the Summit. Allows Sasquatch messages to directly load rows in ConsDB tables. Include a flexible metadata key-value schema for ongoing development.

Deploy Sasquatch connector at the USDF.

Deploy exposure/visit-based summarization at the USDF. Complete prototype code to include more flexible time windows per topic and additional aggregators.

Medium-Term#

Deploy time-based summarization at the USDF.

Figure out relationship between Felis descriptions and Sasquatch Avro schemas.

Generate Alembic schema migrations from Felis updates.

Generate TAP Schema from Felis and load, making ConsDB accessible from RSP.

Dump the database to Parquet files for use by Data Release Production

Provide live logical replica of the database for data rights holders as part of the Prompt Products,

Load static snapshot of the database for data rights holders as part of Data Releases.

Longer-Term#

Figure out replication to Prompt Products and Data Release.

Load other LFA datasets if needed.

Augment CAOM and ObsCore tables as needed.

There may be a need for a tool to help make tagged collections or data id tables out of ConsDB query results.

Deployment at USDF#

First the values file in Phalanx was created namely values-usdfprod.yaml <https://github.com/lsst-sqre/phalanx/blob/63377b6ae3d8661589ebf4c019232982785c8ec6/applications/consdb/values-usdfprod.yaml>

Secret was created in the USDF vault <https://vault.slac.stanford.edu/ui/vault/secrets/secret/show/rubin/usdf-rsp/consdb> with values from base.

Set ConsDB to true in the phalanx environments values-usdfprod.yaml.

Seems database schema exists already.

Also found the S3_ENDPOINT_URL was not being set so this was added to values and assigned in usdfprod and base.

Deployment at Summit#

Set consdb to true in the phalanx environments values-summit.yaml.

Created values file in Phalanx values-summit.yaml <https://github.com/lsst-sqre/phalanx/blob/63377b6ae3d8661589ebf4c019232982785c8ec6/applications/consdb/values-summit.yaml>

Secret added in summit vault ‘summit-lsp/consdb <https://vault.lsst.cloud/ui/vault/secrets/secret/kv/k8s_operator%2Fsummit-lsp.lsst.codes%2Fconsdb/details?version=1>

Create Schema#

For consistency the schema file used at the base generated from Felis and post-processed with the post.sh script was used.

With Summit VPN connected:

psql -h postgresdb01.cp.lsst.org -U oods butler

butler=> \i summit-latiss.sql

\q

done.

Making the schema#

Eventually Felis will do the complete creation of the schema directly. For now we are running it to produce a file. That file is slightly processed and then used to create the schema in the different databases.

Clone <git@github.com:lsst/felis.git> and install it with:

pip install .

Clone ‘git@github.com:lsst/sdm_schemas.git’

The LATISS part of ConsDB schema is in ‘yml/summit-latiss.yaml’.

To produce the DDL run Felis in “dry-run” mode as follows:

felis create-all --engine-url='postgresql://butler:nopass@postgresdb01:5432/butler' --dry-run yml/summit-latiss.yaml >> tmp.sql

Felis puts quotes on names which make them case sensitive in postgres; we remove those with:

yml/post.sh tmp.sql >> summit-latiss.sql

Now we have the schema file we can use in any of the DBs.

Note that the cdb_latiss schema is dropped and recreated by this script.